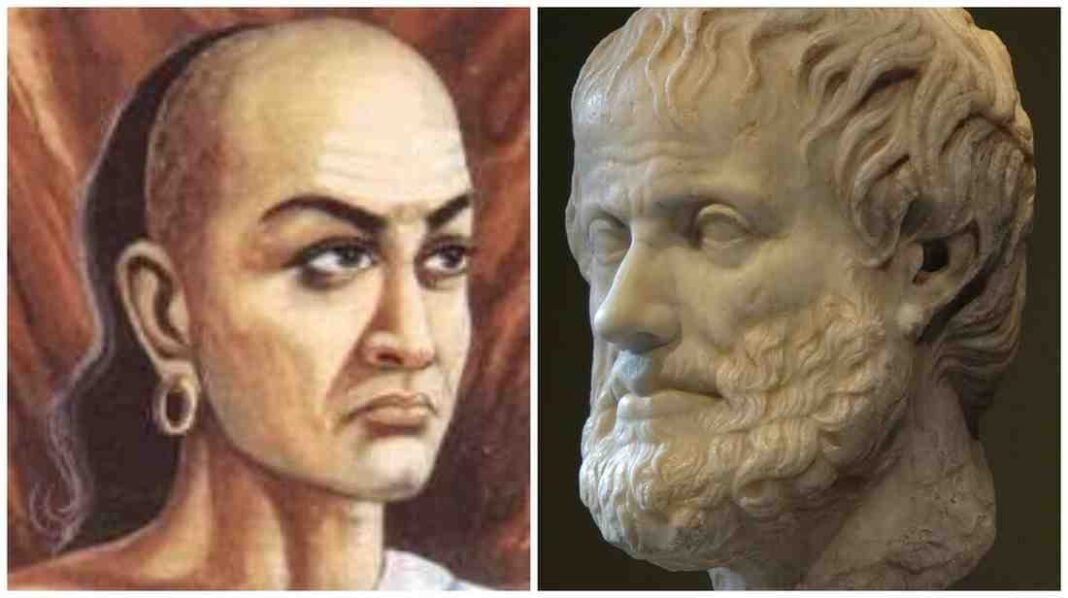

Kautilya of India and Aristotle of Greece reveal that the art of statesmanship is deeply rooted in timeless wisdom. While contemporary international relations and political economy draw heavily from modern theorists, these ancient thinkers continue to offer enduring insights into leadership, governance, and the complexities of statecraft.

In an age where global politics is shaped by rapid technological change, shifting alliances, and economic interdependence, the need for grounded principles of leadership and governance has never been greater. Their philosophies remind us that, despite the evolving nature of global challenges, the core values of effective statesmanship remain constant.

In today’s geoeconomic and geopolitical landscape, where the global political order faces increasing volatility, revisiting their insights offers invaluable lessons on the principles of statesmanship and the interplay between political ethics, governance, economics, and foreign policy.

Kautilya’s Realpolitik and Strategic Prudence

Kautilya authored the Arthashastra in the 4th century BCE, a treatise often considered India’s answer to Machiavelli’s The Prince (though it predates it by nearly two millennia). The Arthashastra is a comprehensive manual on statecraft, encompassing governance, economics, military strategy, and foreign policy.

Central to Kautilya’s vision was the mandala theory, which argued that neighboring states are natural rivals, while distant states can be potential allies. This pragmatic recognition of geopolitical realities mirrors modern balance-of-power strategies. His emphasis on artha (material prosperity) as the foundation for political stability parallels the economic priorities of contemporary nation-states.

Kautilya also underscored the importance of a ruler’s moral responsibility — protecting citizens, maintaining law and order, and promoting economic growth. Yet, he was unflinching in his acceptance of deception, espionage, and strategic coercion when necessary, showing a blend of idealism and realism rare in political thought.

Aristotle’s Virtue Ethics and Political Community

Aristotle, writing in the 4th century BCE, approached politics through the lens of virtue and the flourishing of the polis (city-state). In his Politics, Aristotle envisioned the state as a moral community aimed at achieving the good life (eudaimonia) for its citizens. Unlike Kautilya’s power-centric approach, Aristotle saw governance as inherently ethical, rooted in justice, fairness, and civic participation.

Economic thought also found a place in Aristotle’s philosophy, though framed through a moral filter. He distinguished between oikonomia (household management for well-being) and chrematistics (wealth accumulation for its own sake), warning that the latter could corrupt political life.

His cautionary stance on excessive commercialism still holds relevance for today’s debates on inequality, corporate power, and sustainable growth.

Intersecting Themes and Contemporary Relevance

While Kautilya and Aristotle hailed from vastly different cultural, economic, and political contexts, they shared a common understanding: governance is a craft requiring skill, foresight, and adaptability. Both recognized that leadership is not merely about maintaining power but ensuring the stability and prosperity of the state.

Kautilya, in his seminal work Arthashastra, posits the state (rajya) as the central and most essential political entity.

His theory is built around the preservation, expansion, and stability of the state, which is seen as the primary actor in international affairs. Similarly, Aristotle, in Politics, emphasizes the role of the polis (city-state) as the highest form of political association, arguing that it exists for the sake of achieving the good life.

Although Aristotle is more normative and focused on internal political order, he implicitly acknowledges the polis as the central unit in external relations.

One of Kautilya’s more controversial yet practical ideas is the endorsement of espionage, deception, and even assassination in the interest of state security and expansion. Morality in foreign affairs, for him, is subordinated to raison d’état.

Aristotle does not advocate such tactics, yet he recognizes that justice within the polis does not necessarily extend to external relations, where reciprocity and equality are often absent. Both thus allow for a dual ethical code: one for domestic politics, another for foreign policy.

Both thinkers emphasize the importance of prudence (pragya for Kautilya, phronesis for Aristotle) as a key virtue of statecraft. Kautilya advises rulers to evaluate their relative strength constantly and to act only when the odds favor success.

Aristotle, too, stresses moderation and the importance of aligning political decisions with practical wisdom to ensure the survival and well-being of the polis.

Kautilya’s ultimate objective is lokasangraha — the welfare and stability of the people through a strong and secure state. For Aristotle, the end goal of political organization is eudaimonia — human flourishing achieved through just and stable governance. Despite differing terminologies and frameworks, both view political order and security as prerequisites for the collective good.

However, their divergences are equally instructive. Kautilya developed a systematic fiscal blueprint tied to statecraft; Aristotle treated taxation as part of broader distributive justice. Kautilya integrated fiscal policy, trade regulation, and resource security into foreign policy, while Aristotle linked economic organization to civic virtue and societal stability.

In the contemporary geopolitical landscape, Kautilya’s realism resonates with strategies adopted by states navigating a multipolar world, where power is contested and alliances are fluid. Aristotle’s insistence on a relatively more ethical governance offers a counterbalance, reminding policymakers that legitimacy and social cohesion are as vital to long-term stability as military or economic might.

Kautilya might be seen as a strategic adviser in high-stakes diplomacy, while Aristotle would be the advocate for democratic participation and ethical governance structures.

Both thinkers also highlight the interplay between economics and politics — a reality as accurate today as it was in the ancient world. Whether in designing foreign aid strategies, negotiating trade pacts, or managing global institutions, the fusion of pragmatic statecraft and moral purpose is essential.

Conclusion

Examining Kautilya and Aristotle side by side illuminates the enduring tension in political thought between realism and idealism. Practical statesmanship, as their legacies suggest, demands a synthesis: the capacity to act decisively in pursuit of national interest, tempered by the commitment to justice, institutional integrity, and the welfare of citizens.

In a global order increasingly shaped by geo-economic rivalries and shifting power dynamics, these ancient perspectives continue to make their presence felt.